Protopia Vol. V: The Learning Societies

When machines inherit labor, humanity’s vocation becomes the cultivation of consciousness itself.

Introduction: The Great Inversion

The automation wave has crested.

Current projections suggest that artificial intelligence systems could displace 300 million jobs globally by the mid-2030s, with some researchers predicting near-total automation of human labor within the century.

This transformation makes obsolete not merely jobs, but the entire structure of industrial education, that 200-year experiment in producing compliant workers for predictable tasks.

What emerges in its place?

Not the absence of purpose, but its radical reconstruction.

Three questions guide my exploration today:

How do we learn when learning itself becomes our primary cultural output?

What replaces grades and credentials when economic survival no longer depends on them?

How might education transform from preparation for life into life itself?

Today I examine three functioning experiments—evolved from existing initiatives in Kerala, Copenhagen, and Indigenous territories of British Columbia—each pioneering distinct answers to these questions.

These speculative futures build upon real foundations: Kerala’s alternative education movement, Denmark’s robust apprenticeship system, and Indigenous place-based learning models that have operated for generations.

Case Study I: The Knowledge Commons of Kerala

System Overview

Concept:

Building on Kerala’s long tradition of educational innovation and community-based learning, this distributed ecosystem allows citizens to earn Universal Basic Income supplements through verified knowledge contributions, peer teaching, and collaborative research projects.

Problem Addressed:

The paradox of abundance—when machines handle production, how do we distribute resources while maintaining human agency and growth?

Practical Implementation

How it Works:

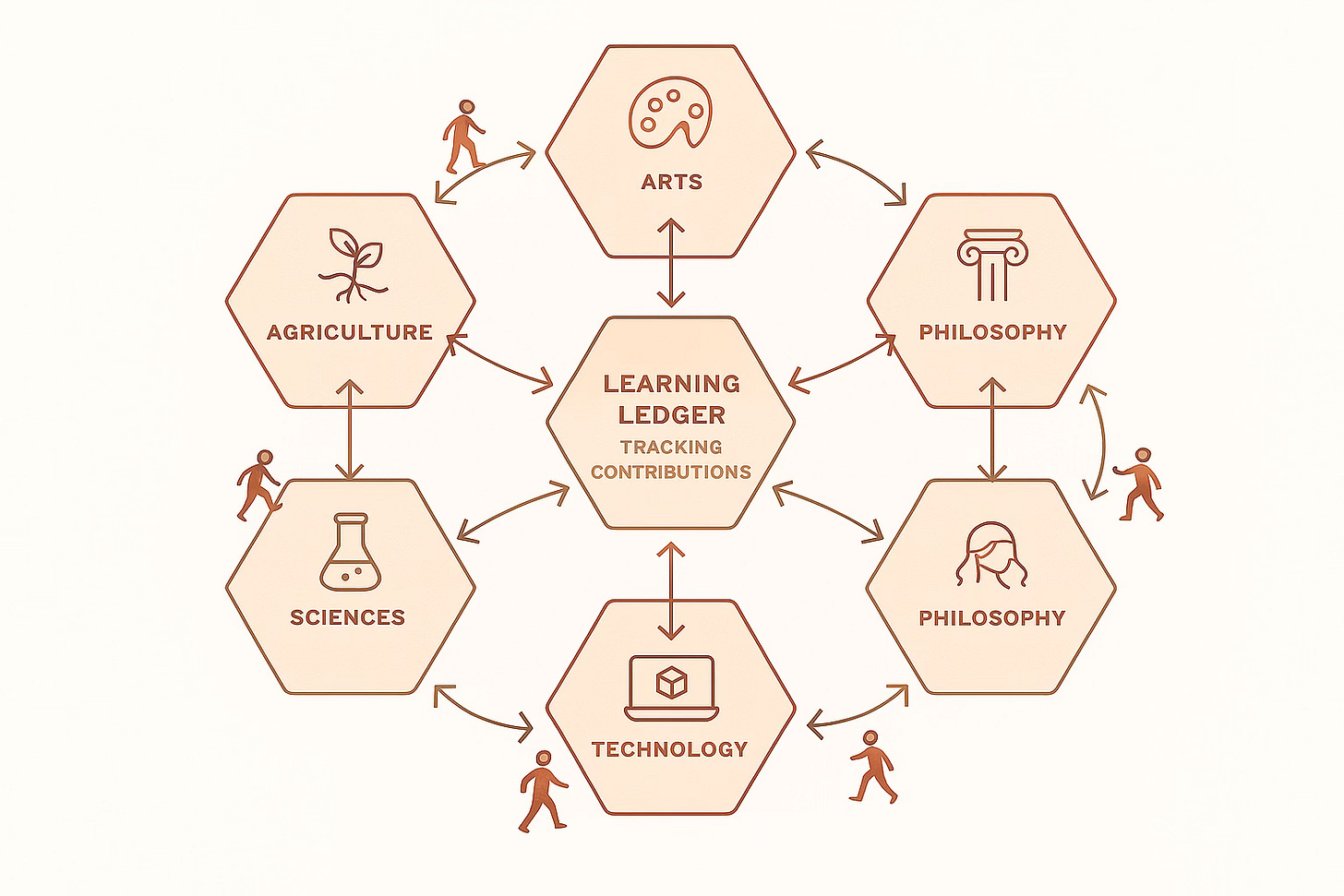

Evolved from Kerala’s existing alternative schools like Sarang and Pallikoodam, which emphasize experiential learning and community engagement, every resident above age 12 receives a “Learning Ledger”—a blockchain-verified record of knowledge created, shared, and validated by peers.

Contributing original research, teaching skills to neighbors, or documenting traditional practices earns “Wisdom Credits” convertible to additional income beyond the basic guarantee.

Key Components:

The system operates through neighborhood “Knowledge Nodes”—repurposed office buildings now serving as combination libraries, makerspaces, and recording studios.

This builds on Kerala’s existing network of alternative learning spaces that already blur boundaries between formal and informal education.

Each node specializes in different domains: Ayurvedic medicine (drawing on Kerala’s traditional medical heritage), regenerative agriculture, speculative engineering, philosophical inquiry.

A Day in the Life

Priya wakes at dawn, not from obligation but anticipation.

Today she’ll finish documenting her grandmother’s pickle-making techniques in the kitchen studio, earning credits while preserving cultural memory—a practice inspired by existing programs at schools like Kanavu that integrate traditional knowledge.

After lunch, she attends Marcus’s workshop on mycelium architecture—he’s visiting from the Lagos node, cross-pollinating ideas.

By evening, she’s deep in collaborative research on monsoon pattern shifts, her meteorological insights valued equally with those of former professors.

Her learning ledger grows not through test scores but through genuine contributions to collective understanding.

Case Study II: Copenhagen’s Apprenticeship Archipelago

System Overview

Concept: Expanding Denmark’s existing vocational education and dual-training system into a citywide mentorship network where citizens of all ages pair for three-month intensive skill exchanges, creating chains of teaching and learning that span generations.

Problem Addressed: The isolation epidemic and lost intergenerational wisdom transfer as traditional workplace mentoring disappears.

Practical Implementation

How it Works: Building on Denmark’s current apprenticeship system where students alternate between school and workplace training, an AI matching system pairs learners with teachers based on complementary interests and compatible teaching/learning styles.

This extends existing programs like the Greater Copenhagen Career Program and IDA Mentor beyond professional contexts. Every citizen commits to being both mentor and apprentice simultaneously—teaching what they know while learning what fascinates them.

Key Components: The program operates through “Learning Lighthouses”—distinctive buildings scattered across Copenhagen where apprenticeships occur, inspired by Denmark’s existing vocational schools and mentorship centers. Each lighthouse contains workshops, studios, gardens, and kitchens equipped for hands-on learning.

Digital portfolios replace diplomas, showcasing actual creations rather than credentials, extending Denmark’s current competency-based assessment approaches.

A Day in the Life

Erik, 73, arrives at the Northern Lighthouse carrying his woodworking tools. His morning apprentice, Amara, 16, wants to build furniture from reclaimed materials—echoing Denmark’s existing craft apprenticeship traditions.

They work side by side, Erik’s hands guiding hers through the grain. After lunch, their roles reverse—Amara teaches Erik generative AI art, helping him transform his sketches into animated stories for his grandchildren.

Neither thinks about grades or graduation; they think about the chair taking shape, the story coming alive, the satisfaction of knowledge passing between generations like breath.

Case Study III: The Play Protocols of Haida Gwaii

System Overview

Concept: Building on Indigenous education principles already practiced at the Haida Gwaii Institute and traditional learning approaches, this experiment integrates learning entirely through elaborate games, simulations, and creative challenges that encode practical skills within playful frameworks.

Problem Addressed: The motivation crisis—how to sustain lifelong learning when external pressures (grades, job requirements) no longer compel it.

Practical Implementation

How it Works: Expanding from the Haida Gwaii Institute’s place-based education model and Indigenous approaches to learning through story and experience, the community has developed hundreds of “Learning Games”—from week-long forest simulations teaching ecology through role-play, to construction challenges where teams build actual structures while competing for aesthetic innovation. This builds on traditional Indigenous pedagogies that have always integrated learning with cultural practices, storytelling, and connection to land.

Key Components: The system centers around “Play Councils”—rotating groups of game designers who craft new challenges monthly, inspired by traditional Haida governance structures and the collaborative approach of programs like Learning Circles: Local Food to School. Games integrate traditional Indigenous knowledge systems with contemporary skills: a salmon run simulation teaches both spawning cycles and supply chain logistics; a potlatch game develops both generosity ethics and economic modeling abilities.

A Day in the Life

The dawn drum signals game day. Jordan joins forty others at the community center, uncertain what today’s challenge brings. The Play Council announces: “The Mycelium Web”—teams must build underground communication networks using only natural materials while playing forest organisms protecting against drought. By noon, Jordan’s team has constructed an elaborate root system while learning soil chemistry, network theory, and collaboration strategies—reflecting the Haida principle of Sḵ’aadG̱a G̱ud ad is (learning together). Learning feels less like education and more like being intensely, joyfully alive.

Architecture / Mechanics

Conclusion: The Pedagogical Turn

These three experiments—Kerala’s knowledge commons, Copenhagen’s apprenticeships, and Haida Gwaii’s play protocols—represent speculative evolutions of existing educational innovations. They build upon real foundations: Kerala’s documented success with alternative education improving life skills, Denmark’s robust vocational training system, and Indigenous pedagogies that have sustained knowledge transmission for millennia.

Current research on Universal Basic Income, from OpenResearch’s comprehensive U.S. study to pilot programs globally, suggests that financial security enables rather than discourages meaningful activity. Recipients tend to pursue education, entrepreneurship, and community contribution when freed from survival pressures. These educational futures imagine how such freedom might reshape learning itself.

Yet tensions persist. How do we ensure equity when some communities have richer knowledge traditions to draw upon? Can intrinsic motivation truly sustain lifelong learning for everyone, or will some require external structure? Most critically: in celebrating human creativity and wisdom, how do we avoid creating new hierarchies based on intellectual rather than economic capital?

These are not questions to answer but to live with, to test through implementation. The seeds of these futures exist today in alternative schools, mentorship programs, and Indigenous education initiatives worldwide. What might bloom in your community? What learning experiments are you ready to plant?

Notes & References

Alternative Education Models

Pathak, S., & Kumar, P. (2022). “Alternative and mainstream education in Kerala: A comparative study based on life skills of students.” International Journal of Educational Development, 89, 102532.

Nair, J. (Ed.). (2023). Un/Common Schooling: Educational Experiments in Twentieth Century India. Oxford University Press.

“Alternative Schooling in India: A Working List” (2023). Bloon Toys Educational Resources. Available at: bloontoys.com/alternative-schools-india

Apprenticeship and Mentorship Systems

Karlson, K.B., & Eriksen, J. (2025). “The making and unmaking of opportunity: Educational mobility in 20th-century Denmark.” The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 127(3), 456-478.

Indigenous Education Approaches

Archibald, J. (2022). Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit (2nd ed.). UBC Press.

Powell, M., et al. (2022). “Implementation of the Learning Circle: Local Food to School Initiative in Haida Gwaii, British Columbia.” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 11(3), 145-162.

Automation and Universal Basic Income

OpenResearch (2024). Unconditional Cash Study: Three-Year Results from the Largest UBI Trial in the United States.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2018). The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. W. W. Norton & Company.

McKinsey Global Institute (2023). “A new future of work: The race to deploy AI and raise skills in Europe and beyond” McKinsey & Company.

Yang, A. (2018). The War on Normal People: The Truth About America’s Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future. Hachette Books.

License: Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)